El Dorado was the legendary City of Gold of Spanish explorers: but it’s now thought the “golden one” was instead a person, a chief of the Muisca who was ceremonially adorned with gold. Either way, the implication that gold was plentiful in the Americas.

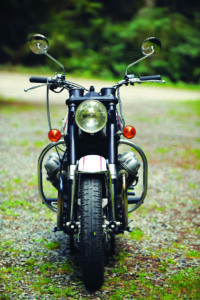

Whether or not Moto Guzzi named their 1972 motorcycle Eldorado in the hope it would find them a metaphorical empire of gold, the cycle certainly built a loyal U.S. following that the Mandello marque enjoys to this day. Much of the Eldorado’s commercial success relied on its being chosen as a police bike by the Los Angeles Police Department and California Highway Patrol.

The Eldorado is a direct descendent of Moto Guzzi’s 1967 704cc V7, imported into the U.S. by the Premier Motor Corporation, a division of the Berliner organization. The pot of gold Joe and Michael Berliner hoped to secure was a contract to supply motorcycles to America’s police forces. Anti-trust rules required forces to call for more than one supply bid, and as there was only one homemade motorcycle maker, Berliner proposed supplying European machines as an alternative. Berliner was the U.S. distributor for Norton, Ducati and Moto Guzzi, and so the company could theoretically have offered machines from any of these firms.

In the early 1960s, the Commando-based Norton Interpol was still some years away, and Guzzi made only singles at that time. So the Berliners turned to Ducati. Their requests of the Bologna company famously led to Fabio Taglioni’s 1964 1,260cc V4 Apollo. While this mighty machine could easily meet police requirements, it proved to have rather more power and speed than was necessary — or good for the tires of the day. Faced with a large, risky investment in tooling for relatively small sales potential, Ducati’s then owners (effectively the Italian government) pulled the plug on further development.

The V7

Moto Guzzi had long been the principal supplier of motorcycles to Italy’s police and military, usually with the 500cc Falcone or Alce. So when the forces requested a new, more powerful motorcycle with exceptional longevity, it would definitely have needed at least one more cylinder. Together with Umberto Todero, Guzzi’s Giulio Cesare Carcano designed a new 90-degree air-cooled V-twin engine. (That the V7 engine was developed from Guzzi’s “mechanical mule” military project is now refuted by most authoritative sources, including marque specialist Greg Field in his book Moto Guzzi Big Twins.)

Carcano’s design followed much automotive practice: The 70mm stroke one-piece crankshaft used a single crankpin, and ran on plain main and big end bearings. The pistons ran in chrome-plated alloy cylinders of 80mm bore. Helical gears drove the central camshaft which operated the four valves by pushrods and rockers. An engine-speed dry clutch drove the 4-speed constant mesh gearbox with final drive by a shaft housed in the right side swingarm.

Also automotive style were the electrics: a belt drove the 300-watt Marelli DC generator mounted in the engine’s “vee”; sparks were provided by coil and distributor; and the engine was spun by a 32-amp-hour battery and Bosch or Marelli starter motor driving a ring gear on the flywheel. There was no provision for a kickstarter — the V7 was the first and only production motorcycle to rely solely on electric start until the Laverda 650/750 of 1968.

The story goes that Joe Berliner first saw the Guzzi twin in Italy in 1966 when it had won selection as a military and police bike for domestic forces. Although the 704cc, 45 horsepower twin was perfect for Italy, it fell short of the 55 horsepower benchmark for U.S. police bikes established by the Harley-Davidson FLH — the default police bike of the time. Regardless, the Berliners wooed prominent U.S. police forces, to the point of providing sample machines at peppercorn prices, and, it’s said, entertaining influencers in Mandello.

Ambassador

To meet the U.S. horsepower benchmark, the importer, naturally, requested more displacement. The 748cc (83mm x 70mm bore and stroke) 60 horsepower Ambassador of 1969 was the result. To emphasize its performance and reliability, Guzzi ran a modified Ambassador around the track at Monza, clocking over 145mph and setting a number of speed and endurance records.

The Ambassador was instrumental in opening the U.S. market for Guzzi, both to police forces and civilian riders, and it sold well. However, it did have some shortcomings. There were only four cogs in the transmission, while most new motorcycles had five. And if 60 horsepower was adequate, then wouldn’t 65 be better?

Eldorado

To capitalize on the Ambassador’s success and keep ahead of the competition, Guzzi increased the stroke to 78mm from 70mm for more power and torque, and reworked the gearbox with five speeds.

Fortunately, the dual-cradle “loop” frame designed for the V7 could handily cope with the extra power and torque. Attached to the front of the “loop” frame was a “tele-hydraulic” fork with two-way damping but no adjustment, while the twin rear shocks had three user settings. Instruments were from Veglia, lights by CEV and turn signals from Lucas. The 8.7-inch (220mm) drum brakes used a twin-leading-shoe setup in the front, and a single in the rear, attached to wire-spoked 18-inch Borrani alloy rims. Lafranconi mufflers kept exhaust noise to a minimum.

The result was the 850 Eldorado of 1972, the bike that was conspicuously purchased by the Los Angeles Police Department, and the California Highway Patrol. And as the Berliners anticipated, the cops were their best salesmen. Although there was some resistance from older patrolmen, younger officers took to the Eldo quickly. Guzzi had worked to keep the center of gravity as low as possible, knowing that was an important factor; and the engine sat forward in the frame, providing stability and offering good legroom.

Cycle World tested an Eldorado in August 1973. “It’s a bike for crossing continents, not states,” they wrote. “It’s a bike that can carry 200 pounds of gear for camping and a passenger at the same time. And, it’s a bike that can eat up 300-mile sections of expressway and leave the rider free from fatigue. Mountain roads didn’t shake our confidence in the handling.”

That said, their tester was less happy with the brakes “The rear unit is overly sensitive. Contrasting this is the front twin-shoe drum, which fades after a couple of panic stops.” (Guzzi replaced the front drum with a disc in 1974.)

Road Rider concluded: “In summary, it would appear that the Eldorado basically has everything that it takes to be a very reliable, dependable machine.”

Successful though the Eldo was with police forces, it has to be said that Harley was going through a bad patch, which may have influenced purchasers: new owners AMF had tried to cut costs and streamline production, leading to labor problems. Product quality suffered, and innovation was stifled, opening the door for competition.

Over the three years the Eldorado was produced, it’s generally accepted that around 15,000 were built, with the majority going to the U.S. The Berliners had found their pot of gold. Ironically, another change of ownership — at Guzzi — sent things in a different direction. Alejandro de Tomaso pulled the Eldorado from the product line in 1975, replacing it with the sportier 850T. Despite Berliner’s efforts, the 850T and triple-disc T3 were never as successful as police bikes.

Rip Van Guzzi

Alan Comfort has been a Moto Guzzi fan for some time, though until recently the Roberts Creek, British Columbia, resident had only owned singles. He runs a late-1940s 500 Astore, and has a 1930s 500S F-head and a 250 Airone in progress. He likes to think of his 1974 Eldorado in terms of the Rip Van Winkle story:

“He fell asleep for 20 years and woke up an old man,” Alan says. “This Eldorado fell asleep for 40 years and woke up an old bike!”

Alan’s Eldo is a 1974 Verzione Polizei but in civilian trim. That means it’s fitted with the police-spec four-leading-shoe front drum brake. It was last registered for the street in 1978 with 7,000 miles on the clock. The original owner had attempted some simple maintenance — presumably a valve adjustment — then re-sealed the rocker covers with silicone. The silicone squeezed out of the joints and got into the oilways, blocking the feed to the big ends, resulting in a seizure and a spun bearing.

The Eldo was sold to a more mechanically inclined owner who had the crankshaft reground, but there the project stalled for many years, with the bike parts stored in a shed.

Alan picked up the bike as a rolling chassis in 2019 with the engine in pieces. “After a six-hour search of the shed, I found most of the parts,” Alan says. “The bike had been stored in less than ideal conditions. It suffered from corrosion on the aluminum parts and rust bleeding out from under the paint.”

“I briefly considered restoring the sheet metal parts with new paint, coach lining and logos, but that would make the frame, alloy parts, plated parts, switchgear, cables and exhaust look tatty. A $2,500 paint job would soon turn into another $5,000 expenditure in plating, powder coating, polishing and replacement parts; none of which would improve the reliability or rideability of this bike. Not to mention that they are only original once. I convinced myself that a full restoration could be seen as vandalism!” Alan says.

Alan then spent “many hours” with 0000 steel wool and Scotchbrite pads to bring the aluminum and plated parts to a more presentable condition.

Painted surfaces were scrubbed with steel wool and rust preventative, cleaned with soap and water then coated with paste wax with care taken to preserve the original silk screen logos and coach lining.

Meanwhile, Alan was also cleaning the offending silicone from the engine’s oil passages and sludge traps. In went all new bearings, seals and gaskets. Guzzi had originally used chromium plating on the alloy cylinders, but in the damp storage conditions, moisture had gotten underneath the chrome, causing it to start peeling. Alan sourced new Nikasil-coated cylinders, which Guzzi had used from around 1980-on. Also fitted were new pistons, rings, valves, valve guides and seats. The clutch was replaced, as was the drive spline.

Then came time to fit the carburetors. During 1974, there had been a strike at the Dell’Orto factory in Cabiate, near Monza. To maintain production, Guzzi was forced to find an alternative supplier of carburetors. So for a while, many Eldorados, including Alan’s, were fitted with Amal Concentric 930s. Fortunately, Alan knows the British bikes of that era quite well, so the carburetors presented little challenge. The Amals were thoroughly cleaned, gaskets and seals replaced, and reassembled.

“The Amals proved to be serviceable,” says Alan, but “the rubber boot that connects the carburetors to the airbox had perished from age and a replacement could not be found. New boots for Dell’Orto carburetors are readily available, but the boot for the Amal carb is obsolete.”

So Alan set to work and fabricated a new carburetor-to-airbox connector from TIG-welded aluminum tubing and off the shelf plumbing parts. It was painted black prior to installation. “No original Guzzi parts were harmed with this modification!” Alan says.

The original starter motor was badly corroded and beyond reasonable repair, so it was replaced with a pattern part. However, most of the other electrical components were in reasonable shape. The DC generator was brought back to life with a thorough cleaning and lubrication, and new brushes. The voltage regulator was too far gone and was replaced with a new one. Alan also fitted a new distributor cap, rotor, contact breakers, primary wires, plug caps and spark plugs.

Most of the other electrics including the wiring harness and switchgear just required cleaning and lubricating and were returned to service, likewise the throttle, clutch and brake cables.

To make the most of the police-spec four-leading-shoe brake, Alan fitted new brake shoes, then had them “arced” to fit the drums. “After a brief bedding-in period and careful adjustment, the drum brakes have proven to be progressive and powerful,” Alan says. Not surprisingly, it was time to replace the original Pirelli M53 Super Sport tires. Replacements are no longer available, and knowing from period reports that Eldorados can be sensitive to tire choice, Alan fitted Metzler Block C Special Touring tires with Michelin Airstop tubes.

The Lucas turn signals were serviceable with cleaning and polishing, but the plastic lenses needed to be replaced. Fortunately, these are still widely available from British bike parts dealers. The original CEV headlight and taillight were preserved. Alan also repaired and patched a number of tears in the seat cover.

Although the Eldo rides and handles well as it is, Alan plans to dismantle and rebuild the front fork, and the rear shocks are scheduled for replacement. Like many other parts for loop-frame Guzzis, these are readily available and reasonably priced.

So, like Rip Van Winkle, Alan Comfort’s Eldorado is something of a time-capsule. In conserving as much of the original componentry and finishes as possible, the Eldorado is far more evocative of its era than a restoration. And like the fairy-tale’s narrator, it tells us a story of times past — but in the present day. MC