Lyrics by Rev Robert Wilkins/ Rolling Stones – Prodigal Son

Well a poor boy took his father’s bread and started down the road

Started down the road

Took all he had and started down the road

Goin’ out in this world, where God only knows

- Engine: 36.4ci (596cc) air-cooled 42-degree sidevalve V-twin, 70mm by 78mm (2.75in x 3.0625in) bore and stroke, 4.5:1 compression ratio (est.), 13hp @ 3,500rpm (est.)

- Top speed: 55mph (est.)

- Carburetion: Single Schebler Model H

- Transmission: 3-speed, hand shift, chain final drive

- Clutch: Multiplate clutch, light oil lubrication

- Electrics: 6v, magneto ignition

- Frame/wheelbase: Double downtube steel cradle/54in (1,372mm)

- Wheelbase: 54in (1,372mm)

- Suspension: Leaf spring-link front fork, rigid rear

- Seat height: 28in (711mm)

- Brakes: 6in (152mm) internal expanding drum rear

- Tires: 18 x 3.85in front and rear

- Weight (dry): 315lb (143kg)

- Fuel capacity/MPG: 3gal/50mpg (est.)

In 1930, the Depression was just starting to take hold in America, and a lot of poor boys started down the road, looking for something better, going West. One was Sammy Pierce. Born in 1913 in Kansas, he became motorcycle conscious early. Sammy worked with Rollie Free (who later set a speed record on a Vincent wearing a bathing suit) at a motorcycle shop in Kansas, and owned a 1926 Indian Scout. His mother had moved to East Los Angeles, and Sammy decided to go live with her. There were various ways to get from Kansas to California in 1930, including passenger trains, Model A Fords, and riding the rails, but Pierce decided to ride his Scout.

Ninety years ago, the national Interstate system had not been invented, most roads outside major cities were dirt, and gas stations could be few and far between. To modern eyes, a 1926 Indian Scout is a museum piece, with a total loss oil system, no front brake and no rear suspension. The Cannonball coast-to-coast rally often features similar bikes, but most riders upgrade their mounts to the limits of the rules and all travel on modern pavement, some with a chase vehicle following behind. Although Sammy went by himself, he was an experienced rider, had good mechanical skills, and his motorcycle was one of the most reliable bikes to be had.

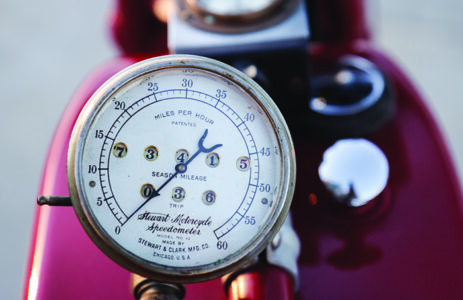

A 1926 Scout is a very simple but tough machine. It was originated by the legendary Indian racer and motorcycle designer, Charles B. Franklin, in late 1919 as a 36.4ci (596cc) 42 degree V-twin. The helical gear primary drive and sturdy double loop cradle frame were big helps on the rough roads of the time. A removable head was introduced in 1925, which made servicing the beast easier. Most motorcycles made before 1928 had a total loss oiling system, and no front brake, so the Scout did not seem unusual. Top speed was about 55mph, but 55mph was probably faster than was safe on most roads of the time.

From before World War I to the beginning of the Depression, Indian, then one of the world’s largest motorcycle companies, had a thriving export business, and many Scouts were sold overseas. To Americans coping with long straight roads, a 37ci motorcycle was a small machine, and the big brother of the Scout, the 61ci (1,000cc) Indian Chief, was preferred by many. To Europeans, riding shorter distances on twisty roads, a Scout had as much horsepower as they needed. The export business was effectively ended by protectionist tariffs enacted in the early 1930s by governments struggling to cope with the spreading Depression. Loss of this market was a major blow to Indian and probably contributed to the company’s demise in 1952.

Scouts today

The Scout was (and is) relatively easy to maintain. In the early days, most motorcycle riders expected to do most of the work on their bikes themselves, and most owners who ride their Scouts continue to do so. Antique Motorcycle Club of America members can download a scanned copy of the 1926 Rider’s Manual from the AMCA website, which has a wiring diagram, lubrication instructions, an explanation of brake and valve adjustment, and several pages on servicing the carburetor.

Richard Ostrander, long-time American motorcycle enthusiast and historian, says, “They really are a simple machine. If the magneto’s hot and the carb processes fuel, it’s ‘heel to squeal’ with the foot clutch and off you go. The top plug, not the bottom one on the left case should be the level of oil in the cases to start with. Air in the tires, battery up, gas and oil in the tanks, good to go.” David Hansen is the owner of The Shop in Ventura, California. David is a source for motorcycle restoration and repair and Indian parts and literature, and he counts Sammy Pierce as one of his two main mentors. “Maintaining a 1920s Scout isn’t hard. You want to use a 50 weight mineral oil, with no additives. I use Aeroshell, made for airplanes. There’s no oil filter, so you want contaminants to fall to the bottom. Drain the oil out of the sump every 2,500 miles or once a year, whichever comes first. Check the valve lash, the bolts, the battery, the spark plug gap and the magneto points gap — that’s about it.”

Scout reliability led to its use in police service in Massachusetts and Pennsylvania. In 1923, riders broke both the cross country and the Canada to Mexico records on Scouts. Given this background, Sammy Pierce’s idea to ride his Scout to the West Coast doesn’t seem quite so crazy — even though he didn’t have enough money to make the trip.

Sammy found some work here and there, enough to pay for gas and food. He also may have entered a few races for the prize money. The Scout broke down in Oklahoma, and a kind gas station owner allowed Sammy to work on his bike in his garage. Sammy noticed metal stamps on a workbench and used them to put his initials on the engine.

It took a while, but eventually, Sammy and his Scout got to Los Angeles. He started a body shop and did some racing. Some time after Sammy got to town, the Scout disappeared. No one alive now is really sure why, or where it was, for over thirty years.

To Kansas and back

Pierce had been writing to a Kansas lady, Lorenna, and he went back to Kansas to see her in 1935. The trip back was probably some combination of Greyhound bus, riding the rails and general hoboing — Sammy was still living hand to mouth. While in Kansas, he took part in some motorcycle races and even promoted at least one. He got a reputation as a fast rider, and a Kansas dealership gave him a race bike to campaign for them. Sammy won enough money to buy an Indian Chief and sidecar, packed up Lorenna in the sidecar, chained the race bike between the Chief and the sidecar and headed back to Los Angeles. They took turns riding the Chief and sleeping in the sidecar, as there was no money for hotel rooms.

Once again, trouble struck in Oklahoma — the dealership that owned the racer had reported it stolen. The pair in the sidecar outfit were stopped by the local sheriff. Luckily, it was lunchtime. The law took the race bike and told Sammy and Lorenna to stay put while he got something to eat. As soon as the man with the badge was out of sight, they hightailed it out of town.

Back in Los Angeles, Sammy and Lorenna got married and had a son, Glenn. Sammy joined the Navy as World War II started and was stationed at a naval base in the San Francisco Bay Area as a mechanic. In his off time, he would customize cars for the officers. His job gave him access to gasoline, a rationed commodity during the war, and Sammy would drive to Los Angeles with jerry cans full of gas in the back. For probably the first time in his life, Sammy was money ahead after he was discharged, and he started an Indian dealership on Garvey Boulevard in the Monterey Park area of Los Angeles.

In the late 1940s, Indian was going down the tubes due to company mismanagement. Despite Pierce’s lifelong love for Indians, he was a pragmatist with a family to support. Pierce sold the dealership to his friend, racer Ed Kretz, and became the Norton importer for the West Coast. Glenn remembers that his after school job was taking the nails out of the motorcycle crates. Sammy used the wood to build two or three houses up the street. “He always had two or three things going at the same time,” Glenn says. He also decided he could do a better job at designing motorcycles than the Indian factory, and came up with the P61 Rocket, using Indian parts, in 1951 and 1952. He built two Rockets, tried and failed to get investors interested, and shelved the project. One of the Rockets has survived.

Sammy never stayed in one place or did one thing very long. Glenn jokes that the family’s suitcases had wheels. He sold the distributorship, moved to Merced, north of Los Angeles, and bought a trailer park outside of the town. He turned a building on the property into a Triumph, BSA and Norton dealership and started making reproduction Indian parts. When the State requisitioned the property for a new freeway, Pierce moved into Merced and started a used car dealership. Two years later, he moved to Fresno and ran a used car lot and a Royal Enfield (then badged as Indian) dealership.

Becoming Mr. Indian

In 1959, Sammy moved back to Los Angeles and started the business that made his reputation as Mr. Indian: an Indian engine restoration shop. Glenn Pierce worked at Sammy’s other business, a new motorcycle dealership on San Gabriel Blvd., which sold a variety of bikes from Parilla to Kawasaki. “In those days, anyone who bought two bikes and a box of parts could call themselves a dealer.” The restoration establishment was in the nearby town of Monrovia, and became well known very quickly as THE place to send a wonky Indian engine. Engines came in from all over the U.S. and sometimes other countries.

In 1968 or 1969, someone in the Midwest sent Sammy a 1926 Indian Scout engine. The mechanic working on it said, “Look, someone put their initials on the engine.” It was Sammy Pierce’s old Scout. Sammy got on the phone with the owner and worked out a deal to send the owner a good Scout engine, the same model as the ’26, which he had in his shop. The shop had all the missing pieces of the Scout, new old stock, on the shelf. Sammy got his old Scout together and got it running, but after a year or so he put it in his living room.

Meeting Steve McQueen

At about the same time that Sammy was reunited with his Scout, he tried to re-start the Indian company. He built up bikes, modernized them a bit and advertised them. Unfortunately, like his previous ventures, Sammy couldn’t get enough investment to make the Indian revival a going thing.

“Harley, Harley, made of tin, ride it out, push it in,” Sammy would say. Through all these ups and downs, Sammy was loudly pro-Indian and anti-Harley. He had a trash can labeled “Harley Parts Bin” and a hammer mounted on the wall labeled “Harley Repair Tool.” He would say that the Harley model VL meant, “Very Lousy.” Pierce’s Indian enthusiasm inspired a new generation of Indian motorcycle aficionados, including David Hansen, AMCA judge Red Fred Johansen and actor by profession/racer by inclination Steve McQueen.

Glenn remembers McQueen coming around on Mondays when the shop was closed to the public. “Father would buy bikes for McQueen, starting in the late 1960s. He would also remanufacture parts for Steve’s bikes. Word got around that Father was buying for Steve, and people would try to jack the price up. That would get Father mad. He would say, ‘Don’t EVER try to buy parts from me.’ McQueen would pay a fair price, but no more.”

Eventually, Steve McQueen started trying to talk Pierce into coming to work for him, to keep the motor vehicle collection up and running. By the late 1970s Pierce was getting older, and running two businesses was getting challenging. After Sammy and Lorenna bought a house near McQueen’s place in Oxnard, north of Los Angeles on the West Coast, Pierce sold his business and most of his bikes and brought three — a Chief, a later model Scout and this 1926 Scout — to Oxnard. It was a pretty idyllic existence for a while, but then McQueen came down with cancer. He died in 1980.

The McQueen family hired Sammy to organize and maintain the collection –which at McQueen’s death numbered more than 200 bikes, 55 cars and some aircraft — until it could be sold. Sammy hired a local kid, Matt Blake, as his assistant. Matt, now the proprietor of the Iron Horse Corral, manufacturer of period correct sheet metal for Indians, credits Sammy with teaching him much of what he knows about Indians, and giving him his start.

After Sammy died in 1982, Glenn sold the Chief and newer Scout and kept the 1926 machine. Glenn is now getting on in years himself. His two sons wanted the 1926 Scout running, so Doug Burnett refreshed the engine and the family started taking the bike to shows. Glenn’s younger son (Sammy’s grandson) has inherited the motorcycle gene and will take custody of the ’26 and Sammy’s other bike, a racer known as the Harley Eater, when the time comes. “We intend to pass it on through the family,” Glenn says. MC