750 Triton

- Engine: 744cc air-cooled, OHV 4-stroke twin, 76mm x 82mm, 60hp +

- Top speed: “Over the Ton”

Street motorcycles have always been much closer to their competition counterparts than cars.

For example, today’s 600cc sport bikes are not much less than Supersport racers without the blueprinting. Not surprisingly, then, any winding road near a major conurbation early on a Sunday morning will find team-suited, replica-helmeted riders dicing for honors.

And with the popularity of clubman’s racing in the 1950s, where riders duked it out on the track on lightly-modified Gold Stars, Matchlesses and Nortons, it wasn’t long before the bars-below-the-instruments look was being copied by young street riders emulating their heroes. And with the loosening of credit purchasing, many British working blokes could afford a pretty fast bike.

It is worth comparing power and performance of the cars and motorcycles of the day. My first car, a 1955 Ford Anglia 100E boasted 32 horsepower from its 1,172cc flathead four, giving it a top speed around 70mph with a strong tailwind. By comparison, a contemporary BSA Road Rocket was good for 42 horsepower from half the swept volume and topped out at over the “ton.” And while a 1964 289 Mustang and 650 Bonneville had similar top speed, the Bonnie was 2-1/2 seconds faster in the standing quarter — and was considerably cheaper! Not surprisingly, impecunious teens with the need for speed were attracted to motorcycles.

Perhaps the most desirable of racer look-alike café bikes was the BSA DBD34 Gold Star in Clubman’s trim. The all-alloy 500cc pushrod single with its heavy finning, swept back exhaust, clipon handlebars and slender fenders created the look that all others wanted to copy.

Café culture

So in Britain the ingredients for the café racer movement were in place: the desire to emulate clubman racers, available high-performance two-wheeled machinery, plus the coffee bars that would serve as start and finish lines, along with a network of arterial and peripheral roads that provided the track.

In pursuit of the right look, all manner of humble machines were pressed into service kitted out with go-faster accessories. If the front fork didn’t lend itself to clip-on bars, downswept “Ace” handlebars (named for the eponymous café) worked just as well. Two-into-one “siamesed” exhaust pipes were plumbed to a reverse megaphone or Goldie-style tapered muffler with its characteristic twittering sound. Slender chrome blades replaced sensible fenders. Likely as not, the standard seat and gas tank would be ditched, replaced with a bump-stop racer’s perch and a 5-gallon production racer style alloy gas tank. To complete the makeover, many added an accessory tachometer, alloy wheel rims, perhaps, and for the real racer look, an Italian twin-leading-shoe front brake.

Engine modifications were typically less adventurous, often little more than ditching the air filter in favor of a bellmouth, and where possible, twin carburetors to replace a single item.

Not surprisingly, Britain’s extensive aftermarket industry stepped up to provide what these new customers wanted. Among them were high-profile clubman racers who, quite naturally, wanted to cash in on their success. The names are legendary: Eddie Dow, Paul Dunstall, Colin Seeley and the Rickman brothers. Each specialized in a particular brand: respectively; BSA, Norton, Matchless and Triumph. But the bike that best expressed the ethos of the café racer belonged not to one brand, nor to one tuner: the Triton.

Hot wheels

It is said the Triton originated in the 1950s with the popularity of Formula 3 and Formula 500 auto racing. These tiny cars used 500cc motorcycle engines, and the best available was the Norton Manx. But Norton declined to sell its engines separately, so F3 car builders had to buy complete motorcycles to get the engine. Suddenly there were available Norton Manx rolling chassis with the famous “featherbed” frame but sans engine.

History doesn’t record who was first to fit a Triumph twin engine into Manx cycle parts, but the combination of the sweet handling Norton chassis (originally made of SIF-bronze welded Reynolds 531 chrome-moly steel tubing) and the simple, reliable, tunable Triumph twin engine caught on quickly. In time, of course, Triumph engines were fitted in featherbed-style frames “borrowed” from more mundane machinery like the ES2, Model 88 and Mercury, and made from mild-steel tube. Fitting the Triumph engine was a relatively simple matter of buying or making a set of engine plates and bolting the parts together — though it had to be done properly to get the best results.

The Dresda Triton

Perhaps the most successful at mating these components was racer and tuner Dave Degens. Starting in Clubman racing with a BSA Gold Star, Degens soon made a name as one of the best riders and builders. Degens’s “Dresda” Triton became the benchmark for hybrid builders, especially when Degens himself with co-rider Rex Butcher won the 1965 Barcelona 24-hour production race. The race bike used a 1962 pre-unit Triumph 650 engine (with a 1965 top end) in 1962 Manx Norton cycle parts. The mildly tuned engine employed stock compression and ordinary Amal Monobloc carbs, but with racing cams and gear ratios. The most exotic component: an Oldani TLS front brake. Degens’s secrets included careful lightening, polishing and assembly; and while he didn’t invent the Triton, his race reputation certainly popularized it.

Degens, with then-partner Dickie Boon, had bought a local scooter sales and service shop, Dresda Autos of Putney, London, in 1963. With the scooter boom winding down, Dresda started building 500 and 650cc Tritons to order, reportedly selling 50 in 1964. Degens always used a Triumph gearbox and preferred fiberglass gas tanks, as alloy tanks were more susceptible to vibration damage. And it was a 500cc single carburetor Dresda Triton that had been meticulously assembled for reliability rather than all out performance that Degens rode in the Barcelona race. Degens also won the Barcelona 24-hour Endurance Race in 1970 with co-rider Ian Goddard and a 650cc Triumph engine in a specially made lightweight Dresda frame. Dresda is still in business.

When Café was King

“Ton kids creed — live fast, love hard, die young,” roared a headline in Britain’s Today magazine in January 1961.

The subjects of the article — the teenage bikers who hung out at London’s Ace Café — might have been forgiven for wondering whom the story was about. The lurid antics described in the tabloids were wild exaggerations of the petty fist-fights and demure fumblings that actually went on.

Regardless, the Ace’s notoriety was imprinted on popular culture, with regular news reports of rowdiness, rumbles and general rudeness in the pulp press. The Ace even featured in a TV cop show. Some suggest the program may have spawned the idea of “record racing,” the subject of that particular episode. Whether life really did imitate art is debatable, but there’s no doubt the Ace’s bikers — damned if they did and damned if they didn’t — were encouraged to live up to their reputation.

Then on Feb. 9, 1961 the Daily Mirror ran a special investigation into the “suicide club” of Ace Café motorcyclists. Public outrage obliged the police to take notice, and they duly raided the Ace on the night of Friday, Feb. 10th. Twenty-one people were charged with minor offences such as unruly behavior, and most escaped with a small fine. But the days of the “ton-up” exploits were coming to a close.

The Sixties were in full swing, while the Ace’s clientele stayed rooted in the “rocker” sensibilities of the Fifties. And a new breed of motorcyclist was on the road. Scooters appealed to fashion-conscious “mods” who were buying them in spades. To the disdain of traditional motorcyclists, they required no weekend tinkering: riders even had clean fingernails. Scooters could be accessorized, but instead of clipons and rearsets it was mirrors, spotlights and sissy bars. It wasn’t long before a certain amount of taunting started, the rockers’ old-fashioned leather look contrasting with the mods’ high-fashion mohair suits and designer shirts. The one was seen as hopelessly ugly, and the other’s fastidiousness as leaning to effeminacy. This mutual disdain, culminated in the seaside riots of 1964. By 1966, the hostility was fading, and while there were occasional outbreaks of inter-group violence, the riots were over. Not even the tabloids could revive them.

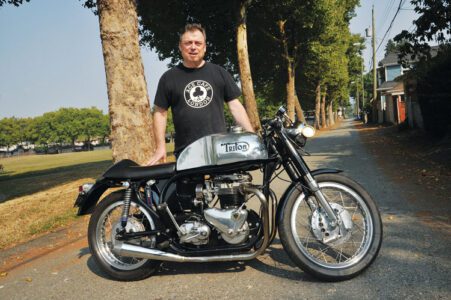

Lionel King’s Triton

Though not a Dresda, the Triton featured here is true to the spirit and interpretation of the breed. And in a rare turn of events, Vancouver, B.C.’s Lionel King received familial encouragement for his acquisition from an unusual source.

It is often the case that spouses are less enthusiastic about their partners’ motorcycle acquisitions. But it was encouragement from his wife Roberta that helped King buy the bike he had coveted for so long.

As a partner in a small import business hit hard by Covid, King was forced to sell his 2010 Thruxton, 1968 Commando, and Triumph Thunderbird. Post-Covid and with the economy improving, King was able to buy a 2017 Thruxton, but the hankering for a vintage British bike, especially a Triton, was still there. That’s when he found one for sale.

“I saw it come up on Facebook Marketplace, and I was just like, “Oh, my gosh. Is that what I think it is?” King was savvy enough to include his wife in the buying process. “I said, ‘Roberta, you got to check this bike out.’ And she said, ‘well you should go look at it,’ and I thought, ‘OK, I just got the approval.'”

“So I went and took a look at it and I just loved it so much, so I bought it. It’s the bike of my dreams. It’s a fabulous bike. I mean, they don’t come along every day. I’ve been looking for ten years.”

The Triton that Lionel bought has an interesting provenance. He acquired it from local British bike enthusiast Stuart Quayle, who bought it from Ross Peaty. However, the previous owner (and presumably builder) was Canadian Motorcycle Hall of Famer John Cooper. As Lionel bought it, the Triton was perfectly roadworthy, but he wanted to make it as reliable and safe as he could. He handed the Triton over to Dave Sundquist of Redline Norton for fettling.

“He did a lot of work on it. And it got a little away on me. I kept going back and seeing the improvements, and I was like, ‘Oh, yeah, this is awesome.’ And when I got the bill … But it’s a bike that I’ll have for the rest of my life. And it wasn’t stupid stuff, but yeah, you know, it gets expensive.”

Lionel’s Triton is titled as a 1961 Norton, but the frame number points to a 1966 Atlas. And while he was told the engine was from a 1963 Thunderbird, the engine number dates it to 1959. Since first built, Lionel’s bike has been extensively modified. Swept volume is now 750cc thanks to 10-bolt 750cc barrels, heads and Hepolite pistons and rings. The Megacycle camshaft features the Sifton 460 road/race profile and actuates Kibblewhite black nitride valves in the bench-flowed cylinder head. Lubrication is by a Morgo high-output rotary oil pump.

The engine breathes through a single 32mm Amal Premier 932 Concentric carb, and sparks are provided by a Boyer electronic ignition. Other modifications include a Podtronics regulator/rectifier and a duplex chain primary drive conversion. The Triton runs on Akront alloy wheel rims (by Morad) with Norton hubs and 8-inch drum brakes, twin leading shoe at the front. Norton Roadholder forks attach the front wheel to the frame, and speedometer/tachometer are Smiths Chronometric.

In spite of all the modifications already made, King still has plans for more. “I need to get new headers, but I’m not sure which,” he says. “The ones that are on there are well-used. I like the short megaphone mufflers, but I’m thinking maybe I want something a little bit more period correct.”

And while swept-back headers would be better aesthetically for a café racer, King also know they would make it harder to work on the engine. King has also purchased a set of 5-speed gearbox internals which will be entrusted to local Triumph and Norton specialist Jim Bush. Does he have any other plans?

“At some point, you know I’ll tear it right down, I’ll clean up the frame and do all of that stuff. But that’s probably a few years away.” MC