Zündapp Bella

- Years produced: 1953-1964

- Claimed power: 7.3hp @ 4,700rpm, 10hp @ 5,200rpm, 12hp @ 5,400rpm

- Top speed: 59mph

In Italy and in Germany, former munitions makers were banned from going back to their previous business after World War II. Companies like Aermacchi, Piaggio, Heinkel, Zündapp and more had to turn to other activities. Piaggio, of course, created the Vespa, selling tens of millions. Presumably, three German industrial companies that entered the same market hoped to emulate Piaggio’s success: Zündapp, Heinkel and NSU.

Until the Vespa and Lambretta, powered two-wheelers had mostly followed similar design criteria. They were essentially heavyweight bicycles with an engine mounted in the middle of the frame. While perhaps the optimal arrangement from an engineering standpoint, it left something to be desired in ergonomic terms. The rider was required to straddle the machine, something that, in some socially conservative countries, could be considered immodest, especially for women: As late as the 1960s, it wasn’t uncommon to see female scooter passengers in rural Italy riding sidesaddle.

What scooters did offer was weather protection, isolation from the noisy and smelly engine, and thus the ability to ride around in a cashmere sweater (just like Audrey Hepburn in Roman Holiday) rather than a grubby waxed cotton jacket. Not surprisingly, then, scooters were a big hit with fashion-conscious Europeans, and they created a whole new market of “non-motorcyclist” riders. Scooters were wildly successful — in 1959, more than half of the new powered two-wheelers sold in Britain were scooters. Every European motorcycle manufacturer had to make one or risk going bust.

The German makers had a similar “advantage” to Piaggio and Innocenti in that they were mostly starting over with the new plant. So when the venerable firm of Zündapp-Werke AG designed a new scooter to be built in its Nurnberg factory, the end result was more sophisticated than most.

Ciao, Bella

Zündapp had been building motorcycles since 1917. Though small commuter bikes were its bread and butter, the company also created the military KS750 “desert elephant” 750cc OHV flat twin sidecar outfit, with reverse gear and two-wheel-drive. Zündapp returned to the consumer market with a new bike: a 198cc 2-stroke single, the DB201.

But what the new riders of the 1950s wanted were scooters. So Zündapp made one: the Bella, appearing in 1953. In styling terms, the Bella paid considerable homage to the pre-existing Moto Parilla Levriere, down to the shape of the swooping side panels and the triangular engine inspection hatch.

Powering the first Bella was a 7.3 horsepower 147cc 2-stroke single with a cast iron barrel and alloy head. The engine drove through a gear primary to a 4-speed foot-shift transmission with a fully enclosed chain final drive, which also formed the single-sided rear swingarm. Shifting was by means of a pair of foot pedals (front for down, rear for up) mounted on the right of the footboards.

Engine cooling was somewhat haphazard though. While on the move, air flowed through a vent in the front of the bodywork, emerging at the back and through louvered side panels. But while stationary, the engine was supposed to rely on the “Thermic Blast” cooling principle, the idea being that the hot cylinder head would create convection currents drawing cool air in through the louvers. Fan cooling, as most other scooters used, might have been a better idea.

The pressed steel bodywork was attached to a tubular frame with a single main spine but with dual tubes running over the engine unit. At the front was a telescopic fork with a spring/damper unit fitted on one side only. The solid alloy 12-inch wheels used 3.50 section tires, giving the Bella more directional stability than most contemporary scooters, while 6-inch drum brakes front and rear provided stopping power. A single seat was standard equipment, though a similar passenger perch could be ordered, and a rear carrier with a spare wheel was also available.

But what the new riders of the 1950s wanted were scooters. So Zündapp made one.

The result was a fairly hefty machine of close to 350 pounds wet, and the 150cc Bella would struggle to get to 50mph. They were well enough regarded, though, for the factory to have built around 20,000 between 1953 and 1955. But the Bella would certainly have benefited from more power, and the factory obliged, introducing a 197cc version, the R201, producing 10 horsepower.

From 1954 on, the Bella was refined and improved with a leading link front fork (but still with the sole spring unit), Denfield dual seat and electric starting. Thus, the final R204, produced from 1959 onward, offered all these features plus an uprated 12 horsepower engine. It remained in this form until production ceased in 1964. MC

Contenders: More alternatives to the Bella

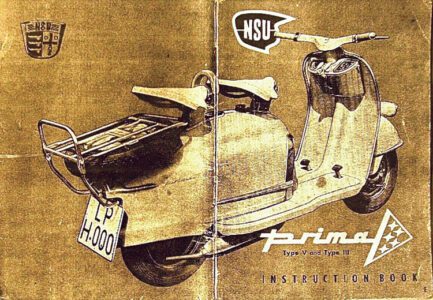

1957-1962 NSU Prima

- Years produced: 1957-1962

- Claimed power: 9.5hp @ 5,200rpm, 6:1 compression ratio

- Top speed: 56mph (Period test: 65mph indicated)

- Engine: 175cc air-cooled 2-stroke single, 62mm x 57.6mm

- Transmission: 4-speed, foot shift, shaft final drive

- Weight (dry): 304lb

- Price now: $2,000-$5,000

In 1951, long established motorcycle maker NSU inked a deal with Innocenti to build Lambretta scooters under license in Germany. But it seems this may have been a feint, as what NSU actually did was “borrow” some of the technology, short-circuiting the process of developing its own scooter. After the license expired, NSU launched the first of its Prima range. The stop-gap Prima D of 1956 featured a 6.2 horsepower 150cc engine, electric starter and pressed steel forks.

The Prima Five Star arrived in 1957 and was effectively a new scooter. Underneath the restyled body was a new 175cc engine, still a single-cylinder but laid horizontally and transverse to the frame with the flywheel on the front. It also featured a 4-speed gearbox, 3.50 by 10-inch wheels, and boasted 9.5 horsepower and 12 volt electrics. In the rear, the engine, gearbox, shaft drive, rear axle and wheel worked as a swinging arm unit controlled by a double-acting spring/damper unit.

“NSU has reached an excellent compromise between good handling and riding comfort,” said Cycle World in a 1962 test. They also found “its cruising speed more than sufficient for safe, prolonged high speed highway driving. The ten-inch wheels … effect an amazing degree of stability.”

The Prima’s equipment was impressive too, with turn signals, spare wheel and luggage rack, even a fog lamp!

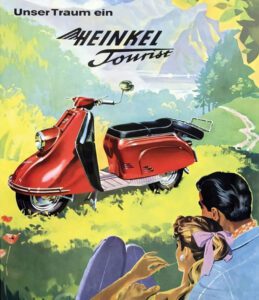

1954-1965 Heinkel Tourist

- Years produced: 1954-1965

- Claimed power: 9.2hp @ 5,500rpm (later 10-12hp @ 5,750rpm)

- Top speed: 60mph +

- Engine: 147cc (59mm x 54.5mm) or 174cc (60mm x 61.5mm) air-cooled, 4-stroke single

- Transmission: 3-speed (later 4-speed), shaft final drive

- Weight: 290lb (1954), 343lb (1960)

- Price now: $3,000-$5,000

Advertised by a Massachusetts dealer, as the “Cadillac of Scooters” the Heinkel Tourist was designed for comfortable long-distance travel. The smooth, quiet 4-stroke single-cylinder engine was rated at 12 horsepower (up from 10 for 1962) and offered plenty of performance considering the size and weight of the machine. However, while its weight was an asset to riding comfort, it made for less than nimble handling. That said, the Tourist was primarily designed to haul two people and luggage or camping equipment in comfort and for long distances.

Surprisingly, given its bulk and weight, performance was quite adequate for highway riding, getting up to speed surprisingly quickly. “Top speed is over 60mph and it imparts a considerable degree of confidence with its excellent stability at this speed,” said Cycle World in a 1962 test, noting that the Heinkel employed a straight telescopic fork rather than leading or trailing arm front suspension commonly found on scooters. The steel tube frame was similar to a conventional motorcycle item, connecting the steering head with duplex tubes over and under the engine. This provided a solid mount for the bodywork. Styling, of course, is a personal preference, and next to contemporary Vespas and Lambrettas, the Tourist looks bulky and ponderous. However, neither Italian competitor had an electric start.

For its last year in production, the engine also gained rubber mounts that almost completely absorbed engine vibrations. “The overall finish is also excellent,” reported Cycle World.